ADHD is not an adaptation

But foraging theory is crucial for understanding it

TL;DR (essential for this topic!)

A long-needed study using a computerized foraging task found variations related to ADHD tendencies but incorrectly concluded that ADHD is an adaptation.

When aspiring evolutionary psychiatry researchers ask for suggestions for good research topics, I have often suggested that they study the foraging patterns of people with ADHD to see if their patch staying times are too short. I was delighted to find a recently published study that used a design very close to the one I advised students to pursue!

Barack, D. L., Ludwig, V. U., Parodi, F., Ahmed, N., Brannon, E. M., Ramakrishnan, A., & Platt, M. L. (2024). Attention deficits linked with proclivity to explore while foraging. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 291(2017), 20222584. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.2584

The design and methods are appropriate. The study was preregistered, and an adequate representative sample of 467 subjects was recruited and studied online using a computerized foraging task and questionnaires about ADHD. The subjects were instructed to get as many berries as possible by deciding, at every instant, whether to stay in a patch as the rate of berry accumulation gradually slows, or move to a new patch, with a travel time delay. Information about which questionnaires were administered when was not provided, despite the risk of demand characteristics influencing the results.

Only 24 subjects reported a previously receiving an ADHD diagnosis, but about half of the 467 subjects had scores on ADHD-associated items high enough to screen positive for ADHD, making the validity of the categorization suspect.

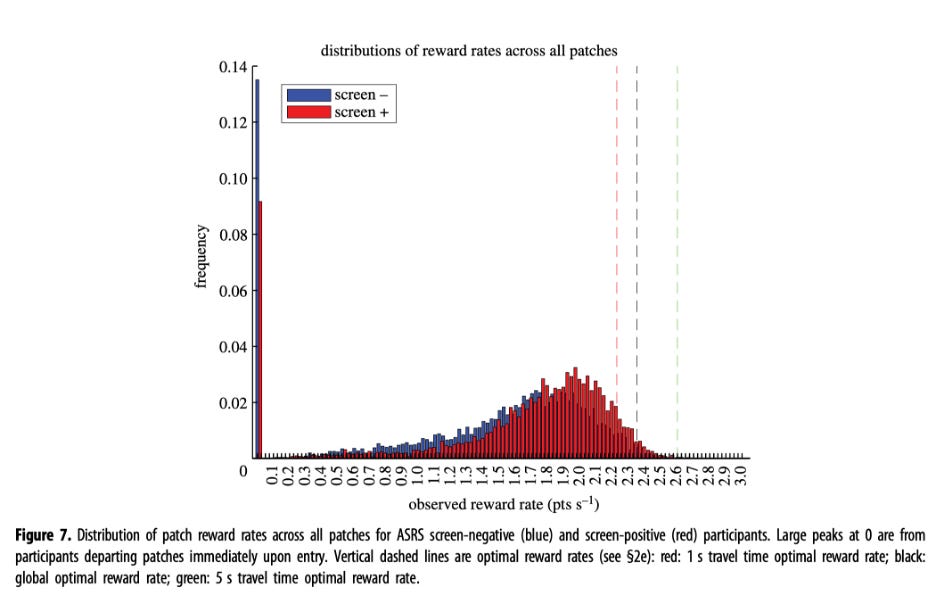

Subjects stayed much longer in each patch than would be optimal. When the delay was 1 second, they stayed an average of 20 seconds, much longer than the optimal durationof 12 seconds. Increasing the delay to 5 seconds increased staying-time to 26 seconds, more than twice as long as the optimum of 12 seconds. While many studies find longer than optimal staying-times, the suboptimality in this study might relate to the very short optimal staying times and the relatively short duration of the trial for each subject.

In the main multivariate analysis, it was a surprise to see that patch staying-time was not associated with the ADHD screening score; instead it was strongly associated with the overall rate of reward. I found this hard to understand given that the overall excessive staying-time for most individuals meant that any tendency to a shorter time would increase the number of berries gained. Another analysis found shorter staying times for those who screened positive for ADHD.

The below illustration shows that individuals who screened positive for ADHD had greater average reward rates than those who screened negative, but both were far from optimal.

These findings are used to support the conclusion that "Consistent with our reported findings, we speculate that ADHD serves as an adaptive specialization for foraging [68–71], thus explaining its widespread prevalence and continued persistence in the human population." (p.9) The last sentence in the abstract phrases the same conclusion a bit differently: " Our findings suggest that ADHD attributes may confer foraging advantages in some environments and invite the possibility that this condition may reflect an adaptation favouring exploration over exploitation."

Leaving aside the findings themselves for now, the hypothesis that ADHD is an adaptation is hard to reconcile with evolutionary theory. Natural selection tends to shape traits to mean values for a species that maximize individual inclusive fitness, so values away from the mean tend to be associated with lower fitness. Of course, environments vary, so fitness may be about the same across a wide range of trait values, especially across multiple generations. Also, across many more generations in a new environment a variation may give a selective advantage that justifies calling it an adaptation. However, these possibilities do not support the suggestion that ADHD is an adaptation that gives fitness advantages.

The logic of this study does, however, make it clear that ADHD associated characteristics have important adaptive consequences. Several viable categories of hypotheses receive support in animal studies. The first is that selection has shaped facultative adaptations that adjust an individual's foraging strategies as a function of experience. This is widely confirmed. The second is that different foraging environments will shape different foraging parameters for different species and different subgroups within a species. This too is confirmed. Both ideas are, however, quite different from the hypothesis that ADHD is an adaptation.

Like most traits, faster or slower shifts in attention have trade-offs, so individuals with trait values away from the mean are expected to get some advantages, along with net disadvantages. Individuals with ADHD tendencies may well benefit from more exploration than other individuals, but that is different from saying that ADHD itself is an adaptation.

In conclusion, the impetus behind the study is great! Variations in ADHD associated characteristics have important influences on adaptation and fitness and experiments based on foraging theory are a great way to study them. But ADHD is not an adaptation.

I'm not ready to conclude that ADHD is adaptive, but I'm also not convinced a trait value being away from the mean is evidence against that trait being adaptive. In particular, I'm thinking about frequency-dependent selection. It could be, for example, that in a population of competitors that tend to explore less, a rare trait of exploring more would allow those individuals access to more resources that haven't been exploited by others and therefore that trait could be beneficial when rare.

Doesn't an adaptation nessecitate a stable definition of a stable phenotype? And considering how nothing in the DSM can be considered a stable definition, I cannot see how a syndrome, or collection of symptoms that changes a lot of over time and seems to have some cultural concept creep in it, can be linked to such concepts as an adaptation? Wouldn't it be better to first create the best possible definition of what is considered ADHD, which can reasonably stay stable over time and be internally and externally valid and accurate before trying to correlate such semi-vague concepts to biological concepts like adaptations? I think that the DSM has enough problems that needs solving before it can be useful to such a degree. Or do you consider ADHD stable and accurate enough for such research? I am interested in what your opinion is about such things.