Mood disorders are control system failure modes

Not products of specific brain abnormalities

Mood disorder research has hoped and expected to find specific brain abnormalities that define specific disorders. Four decades of studies by thousands of scientists supported by billions of dollars have vastly advanced our understanding of brain mechanisms. However, instead of specific abnormalities that cause distinct disorders they have found overlapping suites of symptoms mediated by distributed brain systems responding to diverse situations and multiple causes for failures. Why were expectations so different from what we found?

In the rest of medicine, pathology is understood in the context of the functions of normal systems, and symptoms like pain, cough, and fever are recognized as useful responses. In psychiatry, both of these foundations are missing. Psychiatry has no accepted theory of how mood is gives selective advantages and how it is regulated and therefore criteria that can validate diagnoses. In their absence, mood disorders are diagnosed when the number and severity of symptoms exceeds an arbitrary threshold, without considering situations that may be arousing them. The so-called “medical model” in psychiatry is missing the foundation in understanding normal functions that the rest of medicine relies on.

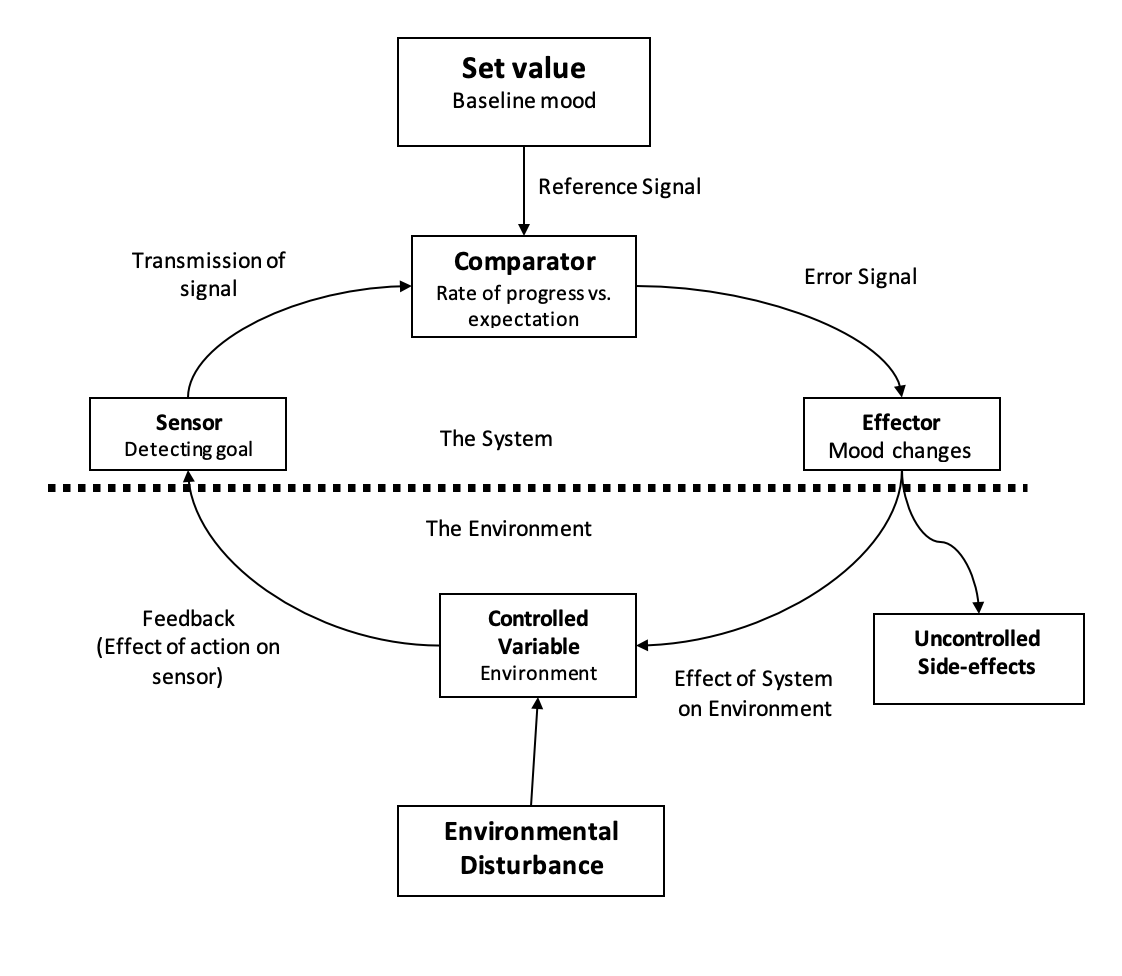

Behavioral ecologists could provide that crucial missing foundation in less than a decade for a fraction of the cost of current research allocations. In the meanwhile, we must make do with a generic framework that can be summarized in three propositions. The optimal amounts and kinds of motivation, effort, and risk-taking vary depending on the situation. Individuals with capacities for special states that meet the adaptive challenges of different situations get fitness advantages. Those advantages have shaped different mood states and systems that regulate their expression. Fitness maximization requires accurately assessing what is needed in a given situation. For humans, that requires knowing an individual’s goals and life projects and expressing various aspects of mood states to the degree appropriate for the situation. Like heart or kidney failures, failures of mood control systems typically result from multiple interacting causes, rather than from discrete abnormalities that could define distinct disorders. The different kinds of mood disorders correspond not to different causes or mechanism flaws but instead to different control system failure modes.

The control systems that regulate mood are far more complex than those that maintain homeostasis. Relatively simple mechanisms monitor body temperature and regulate sweating and shivering. The systems that regulate defensive responses like cough and vomiting are more complex, but detecting foreign matter in the respiratory tract or toxins in the gut is still relatively straightforward compared to processing multiple streams of internal and external information to adjust various aspects of mood to the situation. The task is made exponentially more complex because different individuals pursue different goals in social microenvironments created by constantly shifting relationships.

Beneath the complexity, however, is an important general principle: mood disorders result from control system failures. The different failure modes of control systems should therefore correspond to recognized subtypes of mood disorders. This essay considers ten failure modes for mood control systems and how they correspond to recognized mood disorders. Some reflect the challenge of assessing situations, others from excess or deficient responses, and a few arise from fundamental control system failures.

TEN FAILURE MODES FOR MOOD CONTROL SYSTEM Randolph Nesse 2025

1. The baseline is abnormally low or high

2. The threshold that arouses a response is abnormally low or high

3. Response intensity is excessive or deficient

4. Response duration is excessive or deficient

5. The form of the response is abnormal

6. The system responds to inappropriate cues

7. Responses are expressed in the absence of a stimulus

8. Positive feedback → vicious cycles

9. Oscillation between two extremes

10. Bistability: the response gets stuck at an extremeA control system

Ten failure modes and corresponding disorders

The baseline is abnormally low or high. Chronic low baseline mood is well-recognized as dysthymia; chronic high mood (hyperthymia) is more often envied than investigated or treated. Baseline mood is highly heritable, and it is as stable and as difficult to change as body weight.

The threshold that arouses a response is abnormally low or high. A low threshold for the intensity of cues needed to arouse depression is characteristic of borderline personality disorder but is also present in neurosis.

Response intensity is excessive or deficient. Excessively intense responses are closely related to—but not identical with—a low threshold of response. Deficient responses should decrease fitness but aside from studies of alexithymia and grief, they are rarely recognized as abnormal.

Response duration is excessive or deficient. Chronic grief has been the subject of extensive study, but responses that are too brief are rarely described.

The form of the response is abnormal, for instance when eating and motivation are dramatically lowered without any subjective low mood. Calling such responses “desynchronized” reflects tacit creationism that expects uniform responses and it neglects work by Matthew Keller finding that different aspects of low mood are expressed in different situations in patterns that appear adaptive.

The system responds to inappropriate cues. A depressive response to cues that are not actually germane for an individual is characteristic of neurosis, where sensitized systems constantly scan for hints of rejection or criticism, and express many false alarms. However, other conditions also fit here, such as depression in response to a public figure’s death that will not influence a person’s life.

Responses are expressed in the absence of a stimulus. Apparently autonomous episodes of depression or mania constitute a failure mode that differs markedly from most others discussed here. In this mode a defective control system expresses the emotion in the absence of any identifiable relevant situation. However, the absence of a life event alone is not sufficient to define this mode because inflammation and unconscious processes can be covert provocations.

Positive feedback loops create vicious cycles that make mood disorders worse. Depression escalates and endures when it results in avoiding friends and exercise and not pursuing reachable goals. Severe depression can also change the brain in ways that make future episodes more likely. Mania is often a product of a similar vicious cycle in which success, or the perception of success, increases motivation and risk-taking, causing greater apparent success in a toxic spiral. Other episodes of mania can be autonomous from life experiences.

Oscillation is a failure mode that associated with systems that have very high gain. Modern thermostats use anticipation mechanisms to minimize swings, activating or deactivating a furnace or air conditioner just before the set point is reached. The apparently inexplicable low mood many people experience after a major success may protect against manic escalation. Deficiencies of this damping mechanism may cause the moderate mood swings in cyclothymia. The extreme mood swings in bipolar disorder induce taking large risks in pursuit of grandiose goals. Manic episodes often end abruptly, as if a regulatory mechanism has abruptly suppressed motivation. Such extreme swings are a characteristic of failure modes resulting from excessive gain in the system. Research on subtypes of manic-depressive illness and cyclothymia has steadily expanded recognition that mild mood swings are very common suggesting there may be tradeoffs that maintain somewhat high gain in the system.

Bistability, the tendency for a system to get stuck at one or the other extreme, is also characteristic of systems with very high gain. Its manifestation in bipolar disorder supports the potential importance of this failure mode.

Why recognizing mood disorders as control systems failure modes is important

First, and most importantly, it recognizes aversive emotions as defensive responses similar to pain, fever, and fatigue. That recognition should encourage careful examination of the patient’s motivational structure: values, goals, plans, and how things are going for goal pursuits in each area of life. The S.O.C.I.A.L. list of resources is a useful framework for guiding such investigations; it reveals relevant life situations and equally often, their irrelevance.

Second, framing mood disorders as modes of control system failure promotes analysis at the system level. This approach helps reduce tendencies to assume that different disorders must arise from different specific abnormalities.

Third, different failure modes are likely to correspond to different neural and psychological mechanisms. Using failure mode categories to classify research subjects may yield stronger results.

Fourth, and the topic for a future essay, are the intrinsic vulnerabilities of control systems. Optimal function requires some false alarms, as illustrated by the smoke detector principle. Operation in novel environments often causes control system dysfunctions. And the nature of organically complex systems that makes them robust also leaves them vulnerable to failures, especially from self-adjusting response thresholds that can initiate positive feedback loops creating syndromes including chronic pain.

Finally, analysis in a control system framework emphasizes that organic systems have structures of complexity that are fundamentally different from those of designed machines. Unlike designed machines, which have discrete parts with specific functions, organic control systems consist of interwoven, highly networked components. This organization make organic systems remarkable robustness, but also makes them vulnerable to failures that cannot be traced to abnormalities in any single component.

For a printable PDF, see https://www.randolphnesse.com/nessays

Direction is great. Not clear on all the details but maybe just needs a lot of thinking on my part. Medical model should be about these sorts of frameworks but you are right, currently it’s far off