The Body is not a Machine

This post is adapted from my 2016 essay that inspired the 2025 PNAS Nexus article with Guru Madhavan and Jay Labov on the origins of failure in bodies and machines.

Of related interest: Nesse, R. M., Labov, J. B., & Madhavan, G. (2025). Explanations for failures in designed and evolved systems. PNAS Nexus, 4(4), pgaf086.

The greatest advance in the history of medicine was recognition that bodies are not products of supernatural creation, they are machines assembled entirely from material substances. Now, however, the metaphor of body as machine is an obstacle to progress. To understand the body as a body, we need to blow the metaphor away. Why will be clear only if we first acknowledge its origins and benefits.

The life force: a seductive idea

When death transforms a living breathing body into a cold corpse, it seems obvious that something has gone missing. This mysterious substance has had many names. In 1907 the French philosopher Henri Bergson used the term élan vital, often translated as “vital force.” The idea has endured since the time of the ancient Greeks. Aristotle was preoccupied by the difference between inanimate and living things, perhaps because was the son of a physician to the king of Macedon, the most influential Greek kingdom. The title of his book, De Anima, is usually translated as “On the Soul,” but he viewed the soul as the essence of living organisms, a life force.

A hundred years later, the great Greek physician Galen taught that the special life substance was pnuema, taken in via the lungs and spread throughout the body. He had evidence: when breathing stopped, life ended. For over a thousand years most people in the West went along with the idea that living things have some special life substance that makes them different from inanimate objects. A few pesky early Greek materialists including Democritus and Epicurus thought no such special substance was needed to explain life. However, for most people, for most of human history, it has seemed obvious that living bodies are inhabited by some special life force. It persists today in talk of energy fields. At its root, this “vitalism” is the idea that some special nonmaterial energy or substance is required to explain life.

Leonardo da Vinci: Great Lady

The origins of the machine metaphor

Once dissections became common and anatomical drawings by Leonardo da Vinci and Andreas Vesalius began to circulate in the early 1500s, it became pretty obvious that bones and muscles were just fancy systems of levers, ropes and pulleys. Nothing mysterious, just things. But it was not until the early 1600’s that the French philosopher René Descartes argued for replacing vitalism with scientific materialism. Most people think, “Oh yeah, Descartes. He is the cogito ergo sum guy who created the big nuisance of the mind-body problem, isn’t he?” Yes, that’s him. But give the guy a break! Convincing the world that the body is a machine was a very big deal. He got into plenty of trouble for proposing the radical concept of the body as a machine. Suggesting that the mind too was a machine would have been touching the third rail!

Renee Descartes

As the industrial revolution transformed society, the metaphor of body as machine became increasingly influential. By the start of the 20th century, the idea dominated thinking in biology and medicine, probably because it is so useful. It has improved our lives by encouraging detailed analysis of the body’s mechanisms at all levels, from the details of anatomy, to understanding how hormones like insulin regulate chemicals like glucose. It encouraged reductionism, the idea that everything large could be explained by analysis of smaller things. We are now down to genes, molecules, and atomic forces. What an extraordinary bounty we have reaped from a metaphor! The metaphor of body as a machine provided a ladder that allowed biology to bring phenomena up from a dark pit of mysterious forces into the light where organic mechanisms can be analyzed as if they are machines.

The body is not a machine

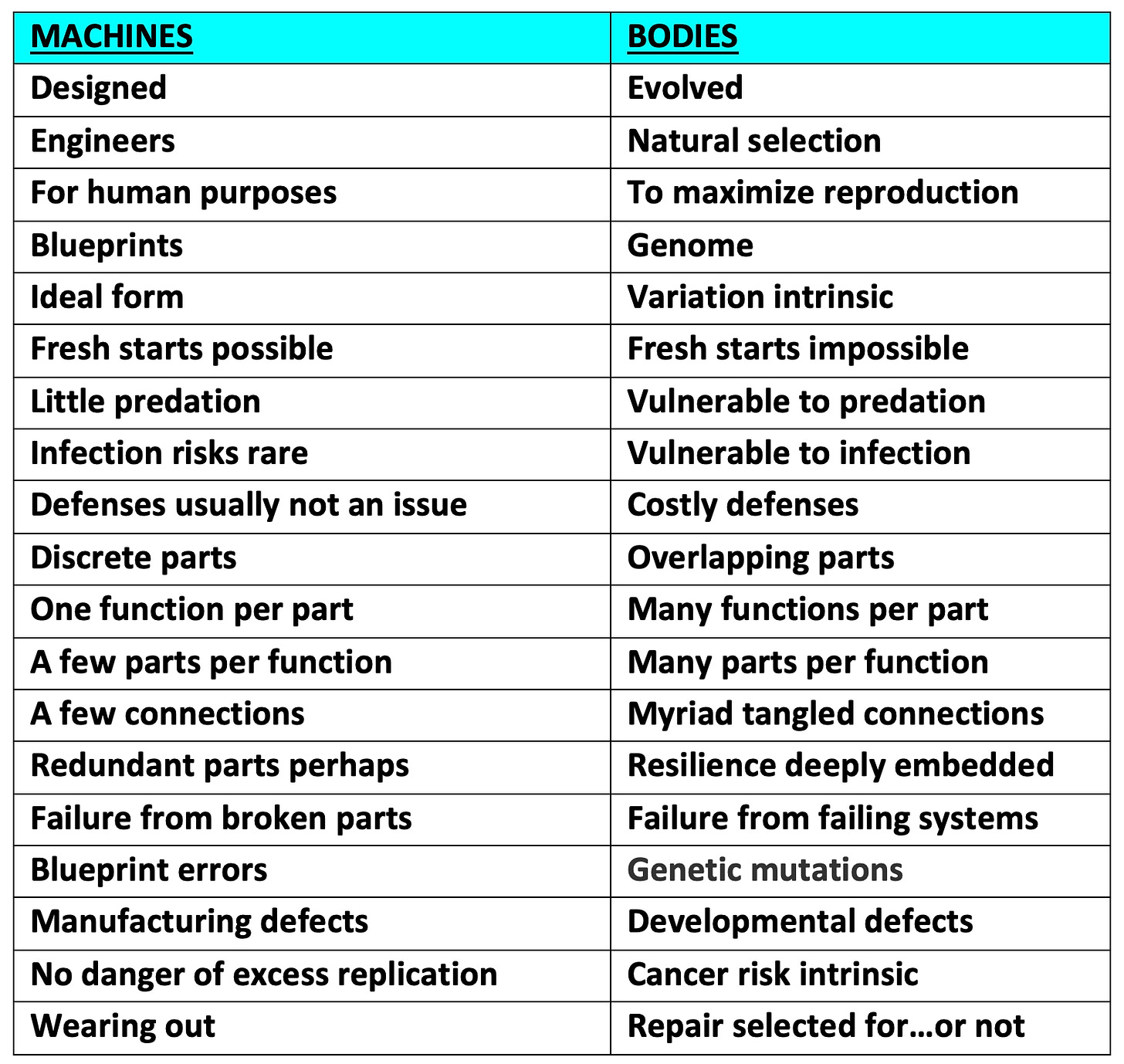

However, the body is not a machine. Machines are products of design, bodies are products of natural selection, and that makes them different in fundamental ways. The organic complexity of bodily mechanisms is qualitatively different from the mechanical complexities of machines. Machines have discrete parts with specific functions connected to each other in straightforward ways. Bodies have parts that may have blurry boundaries and many functions and the parts are often connected to each other in ways hard for human minds to fathom. Bodies and machines fail for different reasons. Engineers can start from scratch if they need to in order to fix weak spot in the design of a machine. If only our human spine could be redesigned from scratch! Its limits and compromises are the source of vast pain, but natural selection can’t start fresh, so we are stuck with a substandard design that can be improved only by small changes. The Table illustrates the substantial differences between machines and bodies. These differences are, however, often ignored, in large part thanks to the power of the metaphor, and the fear that setting it aside will lead to the resurgence of vitalism.

(See our 2025 article in PNAS Nexus for an updated table comparing bodies to machines)

For many scientists, hearing the phrase “the body is not a machine“ is a cue that arouses an almost automatic attack on vitalism. They assume that any derogation of the machine metaphor is an attempt to sneak in vitalism in new vestments. Their wariness is understandable. Naïve talk about the life force or energy fields has to be weeded out of medicine as steadily as crabgrass from a lawn. It is not a big problem. What is a big problem is the metaphor of body as machine; it is as pervasive and pernicious now as vitalism was in the Middle Ages. OK, that is an exaggeration. The metaphor is not AS bad as vitalism. It does, however, distort thinking in ways that slows progress.

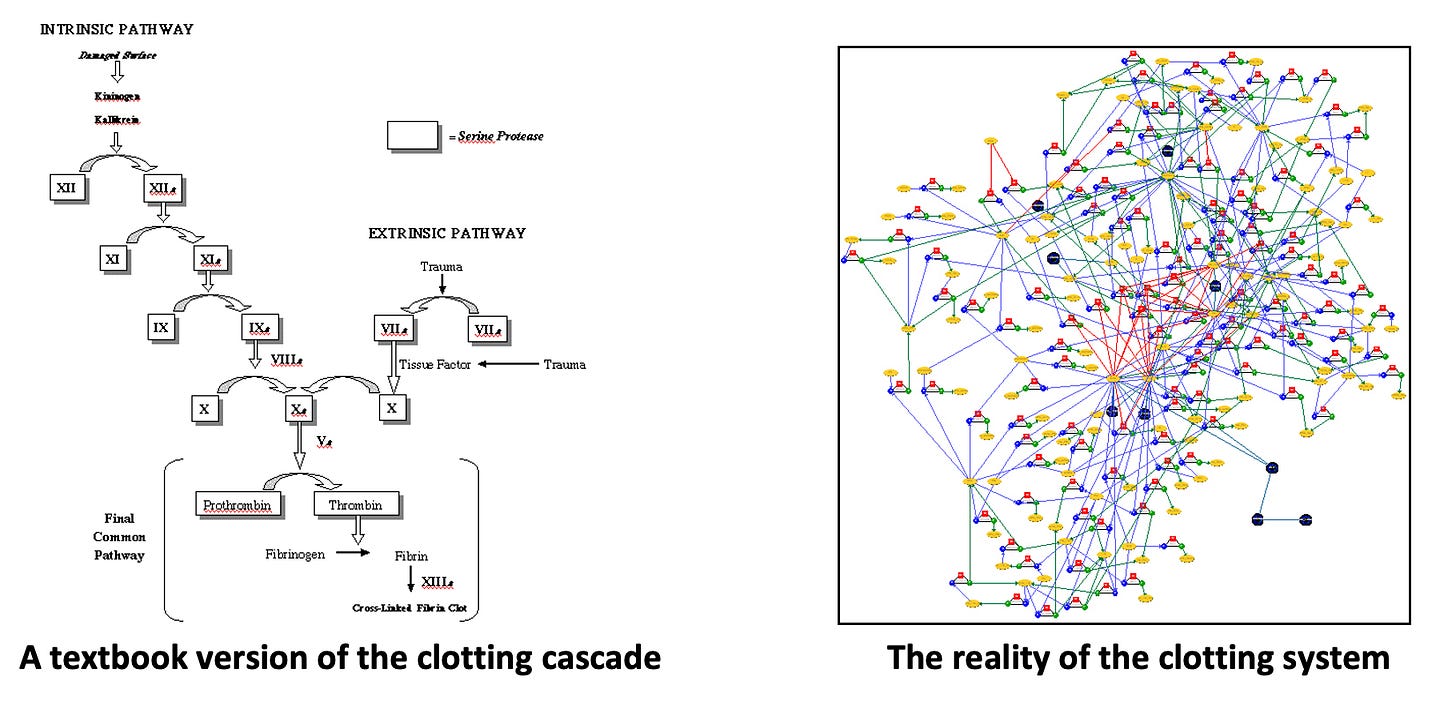

One powerful example is how we teach biochemistry and physiology. We describe systems using idealized diagrams with boxes and arrows. For instance, every medical student memorizes (then forgets) the chain of chemical interactions that make blood clot. This knowledge is essential for understanding clotting disorders, but the diagram is distant from the reality.

Current research often relies on tacit models of body systems as if they were designed. (See my essays on “tacit creationism,” the pervasive tendency to view living systems as if they are products of design, without any reference to supernatural forces.) A multi-billion dollar effort is trying to discover the “wiring diagram of the brain.” But is there a master wiring diagram? The White House Brain Initiative will be more effective if it recognizes that there is no one normal genome, no one normal brain, and no one wiring diagram. Similarly huge efforts are mounted to discover the functions of each location in the brain. The amygdala, a tiny almond shaped area deep in the sides of our brains, has often been described as the locus of fear learning. Yes, if the amygdala is damaged, fear learning suffers. However, many other regions are involved in regulating fear, and the amygdala serves many functions aside from fear learning, including social responses, self-control, aggression, and learning to get positive rewards.

The metaphor of body as machine is a serious error with major costs. In psychiatry, thinking about the mind as a machine has led to a debacle about diagnosis. Many neuroscientists want to abandon the standard system because they cannot find specific brain abnormalities for any of the major disorders. They are sure that for every disease there is some findable broken part. If only. Many mental disorders are, like heart failure, failures of systems with multiple causes and diverse symptoms.

A soma is a soma is a soma

Metaphors are robust. Unless something better is at hand, criticizing the metaphor of the body as machine could be a waste of energy. An alternative metaphor would be ideal, but there is no other metaphor for the body that does not distort reality. Instead of looking for alternative metaphors, we must acknowledge the reality of organic complexity, with its blurry boundaries between bird’s nests of mechanisms. Instead of a metaphor, we must recognize the body as a soma shaped by selection. Soma just means body, so that only helps a little, until we turn for help to the poet Gertrude Stein. Remember her famous, “A rose is a rose is a rose.” She meant it. Eschew metaphor, she said; see the rose as a rose, just the rose itself.

A soma is a soma is a soma, shaped by natural selection. If we can wrench ourselves away from metaphor and see the body as an evolved soma, we can put aside the debates that arise from assuming that its parts have nice crisp boundaries and specific functions. We can avoid further centuries of debates about exactly how many basic emotions they are. Our bodies have parts with blurry boundaries, multiple functions, unimaginably complex connections, and no designer’s purpose underlying the whole system. We teach students distorted versions of biological systems that are simple enough to memorize, and to test! But our diagrams are idealized abstractions that misrepresent reality in fundamental ways. Many organic molecules influence many other kinds of molecules, not just the one to the left and the one to the right in an idealized diagram.

We are on the verge of a transformation. Giving up our idealized view body in the machine will be challenging, but worth it as we accept the reality that a soma is a soma is a soma.

Further reading

Nesse, Randolph M, and George Christopher Williams. Why We Get Sick: The New Science of Darwinian Medicine. Vintage, 1996.

Williams, George C. The Pony Fish’s Glow : And Other Clues to Plan and Purpose in Nature. 1st ed. New York, NY: Basic Books, 1997.

Balleine, B. W., & Killcross, S. (2006). Parallel incentive processing: an integrated view of amygdala function. Trends in Neurosciences, 29(5), 272–279. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2006.03.002

Nesse, Randolph M: Recognizing that the body is not a machine. EDGE annual question essay, 2009. https://edge.org/response-detail/1136.

most relevant disanalogies arise from complexity and evolutionary considerations, but i don't think that naturalists/non-magicalists use the machine metaphor to literally assert that the properties/principles you sort to machines in your paper also apply to bodies. the more charitable interpretation of this metaphor is the more robust claim that bodies (and whatever that exists at all) are MECHANISMS.

Thanks for the article! I enjoyed reading it. Teaching students a simplified version of a complex system is common practice in many disciplines, not just the medical ones. Even in mechanical engineering and physics, where learning to build literal machines is literally the job, students are first taught overly-simplified systems, because it's the most efficient way to introduce difficult concepts. I'm guessing the same is true in the medical world, and students who become more specialized in certain areas are then exposed to a more realistic description of these systems.

I'm not sure the table comparing bodies to machines is entirely accurate, even the 2025 article for PNAS Nexus. Some of the listed differences seem to be more about semantics than actual differences.

Metaphors help people understand complicated, complex, or abstract things. Like stated in the article, without a better metaphor, I'm not convinced that removing the current one would actually help more than it would hurt.