The genotype-to-phenotype path is a maze in a tangled bank

Severely limiting the power of genetic predictions

Randolph M. Nesse

January 6, 2026It would be wonderful if genetic information could predict complex phenotypes accurately, but that looks increasingly unlikely. Missing heritability is substantial, it won’t be explained by newly discovered rare variants [1], and the predictive power of polygenic scores is limited and lower yet in new populations [2].

These limits arise because the path from genes to traits is rarely like the “genes for” model that naively assumes that specific genes code for specific traits. Instead, genes and regulatory regions interact with each other and gene products to create winding paths through a tangled bank of organically complex systems. As Mackay and Arnold dryly conclude in a 2024 review, “relationships between genotypes and phenotypes are often more complex than can be detected with the methods usually employed [3].”

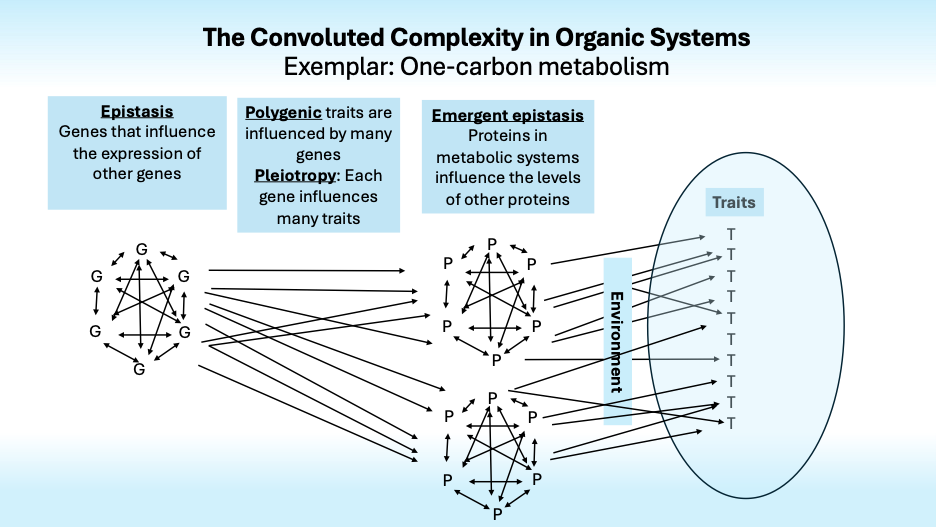

Fred Nijhout and I are working to see if analyzing interaction effects that emerge from a mathematical model of one-carbon metabolism can identify emergent epistasis that could better describe gene → phenotype pathways. A foundation for that project is systematic consideration of the many ways that genes can influence phenotypes. Here is a brief summary.

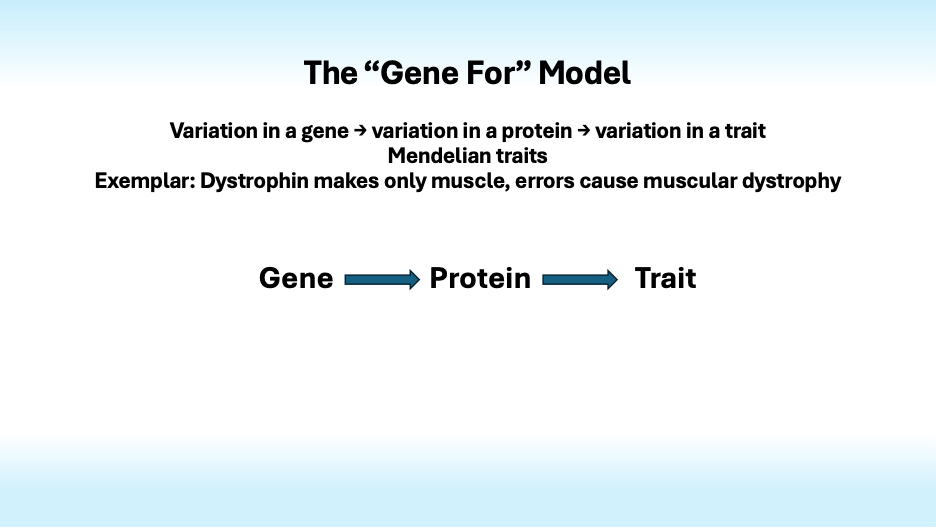

The “Gene for” model, in which variation in a gene induces variation in a protein that causes variation in a trait, is often applied inappropriately to complex traits.

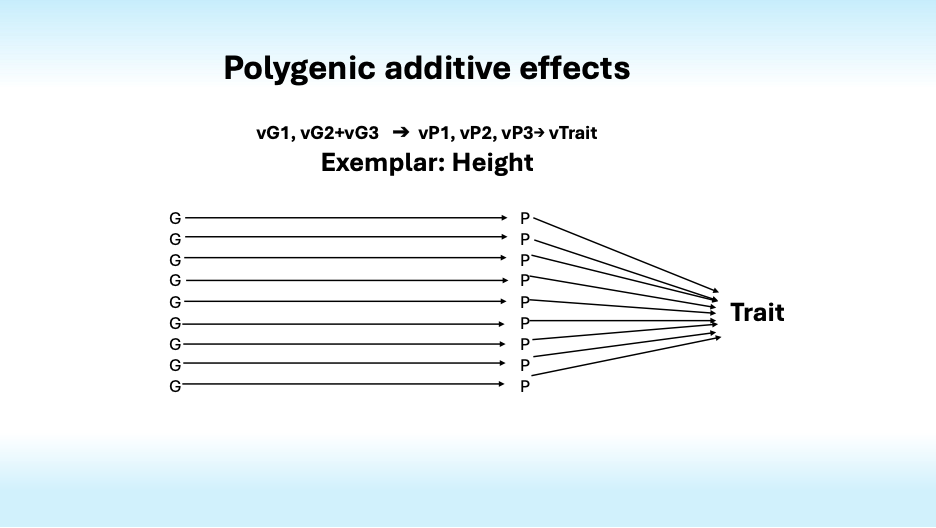

Most traits are polygenic, that is, they are influenced by many genes. For instance, over 12,000 genetic variations influence human height. Together they account for only half of its heritability. What accounts for the rest?

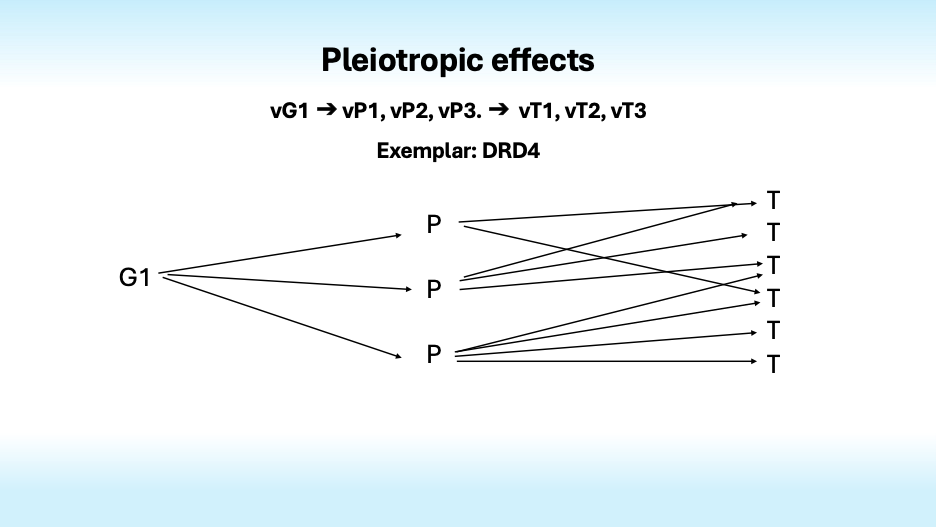

Complexity arises not only because many genes influence one trait, but also because most genes influence many traits. This is pleiotropy. It is especially evident in the findings from studies of mental disorders; most genes that increase the risk of one disorder also increase the risk of others, dashing hopes of finding specific genotypes that could define specific disorders and resolve the confusion that swirls around psychiatric diagnosis.

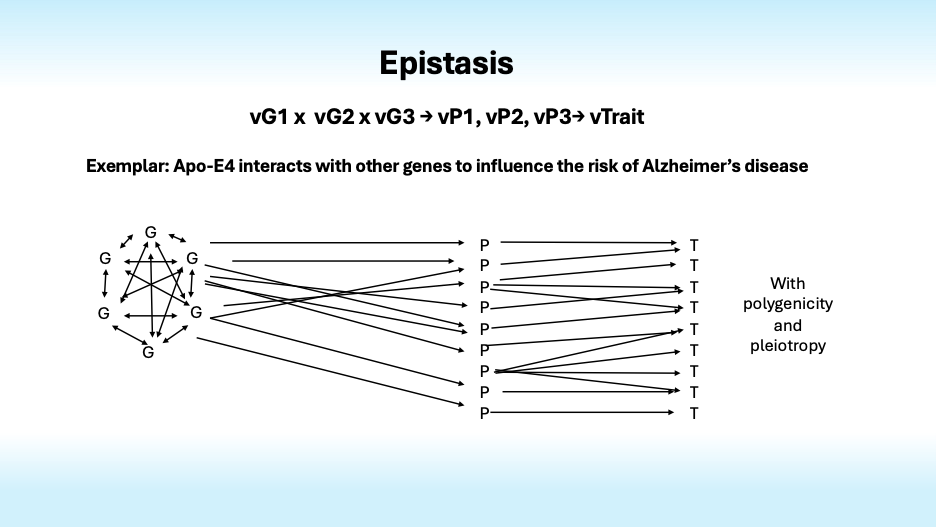

Now it gets more complex fast. As Bateson and Fisher noted nearly century ago, genes influence the effects of other genes, some “standing upon” (stasis) or otherwise influencing the effects of others in ways that create nonlinear epistatic interactions.

Genetic epistasis creates plenty of complexity, but it is augmented by physiological epistasis that arises from nonlinear interactions of genes and enzymes whose activity levels influence gene expression and the activity levels of other enzymes in complex metabolic systems with feedback loops and nonlinear kinetics that interact with each other environments to influence traits.

Finally, we come to the Convoluted Complexity in Organic Systems (CCOS). Its reality is unwelcome, to say the least. It severely limits hopes that genetic information will ever be able to reliably predict disease risk and other complex traits. This may reassure those to those who hate the idea that genes are destiny but it should dismay all of us who had hoped that genetic information would allow diseases to be reliably anticipated and prevented. For prospective parents who are thinking of purchasing a service that sequences DNA from fertilized eggs to enable personalized eugenics, the reality of CCOS encourages rethinking the whole idea.

The conclusion is simple: the pathways from genes to traits are a maze in a tangled bank of organic complexity that fundamentally limit the power of genetic predictions about complex traits. The larger implication is profound: the structure of complexity in organic and designed systems is fundamentally different. Failure to recognize the differences encourages tacit creationism that obstructs progress.

Wainschtein, P., Zhang, Y., Schwartzentruber, J., Kassam, I., Sidorenko, J., Fiziev, P. P., Wang, H., McRae, J., Border, R., Zaitlen, N., Sankararaman, S., Goddard, M. E., Zeng, J., Visscher, P. M., Farh, K. K.-H., & Yengo, L. (2025). Estimation and mapping of the missing heritability of human phenotypes. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09720-6

Kullo, I. J. (2025). Clinical use of polygenic risk scores: Current status, barriers and future directions. Nature Reviews Genetics. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-025-00900-8

Mackay, T. F. C., & Anholt, R. R. H. (2024). Pleiotropy, epistasis and the genetic architecture of quantitative traits. Nature Reviews Genetics, 25(9), 639–657. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-024-00711-3

"Missing heritability is substantial" - that depends on definitions.

ref 1 Wainschtein says ", we find that WGS captures approximately 88% of the pedigree-based narrow sense heritability"

I wrote an in depth piece addressing missing heritability: https://purescience.substack.com/p/missing-heritability-and-the-heritability?r=p3jgh

My conclusion - as GWAS genetic scans expand in N and #genes, the "missing heritability" in narrow sense heritability is disappearing relative to earlier studies. To me, it is a misnomer to call the remaining difference between broad and narrow sense heritability "missing" since by definition, broad sense heritability includes gene-environment and the gene-gene interactions that you discuss.

Good exposition. I think about these same topics constantly, particularly as it pertains to neuroscience and psychiatry. It’s a big topic, and you’ve highlighted good contemporary resources.